#OTD in 1325 peace was declared between England and France. This was the end of the War of St-Sardos in Gascony; a disaster for Edward II and the English, in which the territorial gains of his father were wiped out in a few months.

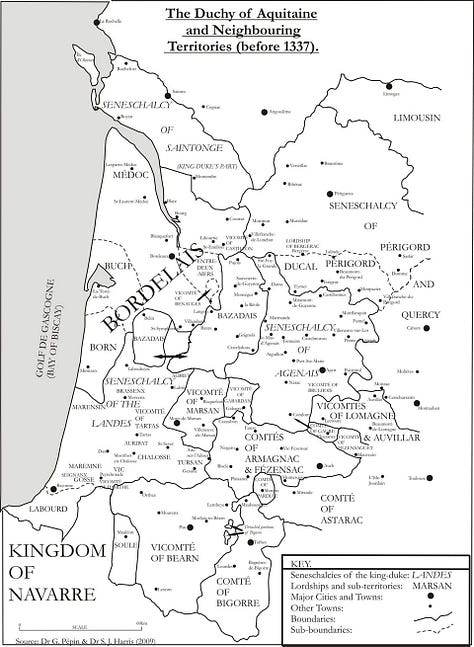

The English war effort had been dismal, and Edward might have lost the entire duchy. He was saved by the Gascon gentry, who rallied to the failing Plantagenet cause. Thanks to them, Edward held onto Bordeaux and the hinterland, though he had to surrender the Agenais, acquired by Edward I via the Treaty of Amiens in 1279. Even this limited gain came at the price of relinquishing Gascony to his son, the future Edward III, who now stood in his father's place as duke.

Edward now had to respond to petitions from dispossessed Gascons. It may seem unreasonable to make comparisons with his father, but the contrast is glaring. After the previous French war ended in 1303, Edward I had responded generously to pleas from his Gascon subjects. Edward II's responses in 1325, in similar circumstances, have been characterised as “excessively mean-spirited and parsimonious” (Dr Malcolm Vale).

His policy is difficult to understand. Edward II had become very rich by this point, after confiscating the forfeit estates of the Contrariants in England. He could afford to be generous to the Gascons who had stood by him, when they might have easily defected to the French. When he failed, some of the more powerful families abandoned him and switched sides anyway. These included the lord of d'Albret, who had personally funded the war efforts against France and served Edward I in Scotland. Without him, the English lost their chief financier in Gascony, while the French gained one. That is not good policy, however you choose to look at it.

Edward II has been caricatured (usually in bad fiction) as weak, unintelligent, cowardly, and a bad husband and father. He was none of these things. As king, it is impossible to defend his record unless you simply ignore all the defeats and failings. Pinning all the blame on his father, Longshanks, a currently unpopular historical figure, is a cheap get-out.

Certainly, Edward II inherited heavy debts and an unfinished war in Scotland. Those debts had no obvious practical effect on his capacity to raise armies and wage war (what he did with those armies is another matter) and after 1315 he became one of the wealthiest kings in Europe. Lack of money was not the cause of his downfall.

As for the Scottish war, Edward junior chose to press it with the same brutality and persistence as his old man, minus the competence. Nobody forced him to. When you look at his policies and decision-making elsewhere, such as the affairs of Gascony, it is the same pattern of bungling and misjudgement. Perhaps it was all someone else’s fault - the laundrywoman? His dog? - but Edward was the king: the buck stopped with him.

A short war, a bitter defeat, and a king who, despite having the resources, made all the wrong moves. The 1325 peace in Gascony didn’t just end the War of Saint-Sardos—it marked the beginning of Edward II’s political downfall. A reminder that pettiness and poor judgment can cost more than any enemy.